The App of the Summer Is Just a Random-Number Generator

TikTok is on the chopping block. Instagram is pointless in lockdown. The best we can do is a hokey piece of software that takes us somewhere unexpected.

It took me a week to find a plastic water bottle full of what could only be pee.

That was after the abandoned house taped off with gas leak warnings, but before I spun around on an unfamiliar block deep in Brooklyn to see three dalmatians wiggling toward me. When I saw the bottle lying in the middle of the sidewalk, it felt like a rite of passage.

This is my summer activity: walking around, or “randonauting” in internet parlance. Water bottles full of pee are known as “piss bottles” in the randonaut community, an inside joke that has inspired T-shirts. It’s pretty simple, as jokes go: If you spend enough time exploring the world at random, you will stumble upon a bottle full of pee.

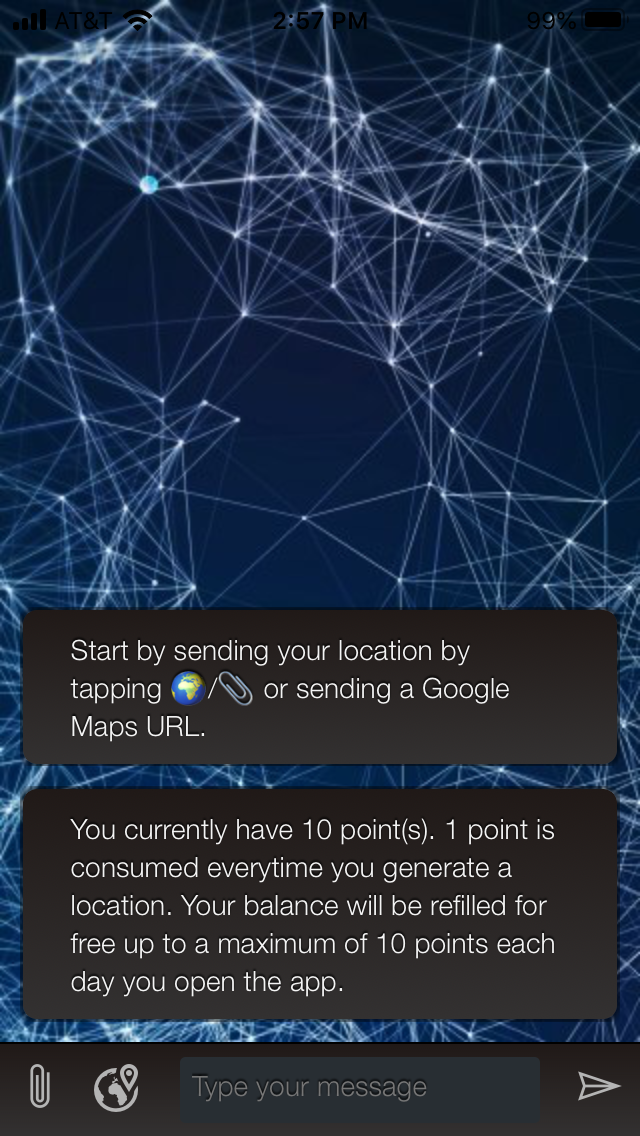

Randonauting is also simple. You can do it using the free app Randonautica, which asks you for your location, prompts you to select one of a handful of different “entropy” generators—which one you choose should not really matter—and then asks you to focus your mind on your “intent.” Then it spits out a set of coordinates that could, allegedly, be influenced by your mind interacting with the machine, or not, and you can choose to go there, or not, and submit a report of what you find, or not. (You can generate 10 sets of coordinates a day for free and pay to generate more.) The app’s logo, fittingly, is an owl, because owls see in the dark; randonauts see what other people don’t. In particular, they see what they otherwise wouldn’t.

Randonautica launched in February and has mixed reviews on the App Store, because it often crashes. Additionally, people who live near bodies of water tend to get coordinates that fall underwater, which can be frustrating. (You have to pay for the privilege of excluding them.) It was created by Joshua Lengfelder, a Texan and former circus performer who told me that the app once took him to an abandoned drum in the middle of the woods, where he nearly stepped on a “bright-red rattlesnake.” “I didn’t even know there were red rattlesnakes in Texas,” he added, understandably, because there typically are not. (Red rattlesnakes are also usually a rust color, or just brown.)

According to the app’s developers, Randonautica has been downloaded 8 million times—6 million since the beginning of April. “That’s really when we started blowing up,” Lengfelder said. “People were trapped in their houses and it gave them a way to break out of their normal routine. It’s one of the few activities you can do while social distancing but still stay safe.”

The allure of Randonautica is bigger than “It allows me to be outdoors and kill time,” however. It is janky-looking, sure, and does not always load. And the science behind it—the idea that human thoughts can influence random-number generators—does not make a lot of sense. But it plays with concepts that people tend to love: that we can do something amazing whenever we feel like it, that the universe will talk to us if we try to listen, and that randomness can be tamed if we have a good attitude and a clear mind.

Though the start of stay-at-home orders in the spring was certainly big for Randonautica, the app really blew up in late June. That’s when a group of teenagers posted a TikTok in which Randonautica led them to an abandoned suitcase that seemed to contain a dead body. (Seattle police later announced that it contained two.) The incident received a smattering of news coverage, including an explainer article on The Cut. More important, it inspired hundreds of TikTok users to start documenting—or staging—their own alarming Randonautica adventures, typically set to music from the soundtracks of scary movies.

“We are somewhere in the middle between a game, science, and art,” the app’s utterly bizarre FAQ page reads. The FAQ is thousands of words long and answers questions such as “Does it go against my religion?” and “I’m scared … will anything bad happen?” (Answers, basically: Maybe and maybe.)

“When you’re sending millions of people to random locations and searching the hidden corners of reality, you’re bound to find some pretty shocking stuff sometimes,” Lengfelder said in response to the dead-body video, pointing out that people frequently stumbled upon human remains during the Pokémon Go craze. “It’s not the best press, but I’m not really that upset about it, because it’s kind of cool. I kind of wish it was me who found it.”

I decided to try the app because of that video. As did Jennifer Costello, a 32-year-old true-crime fan from Vancouver, who was the lucky finder of a plastic bag full of hundreds of photos of moldy bread, which she uncovered in the woods during a rainstorm. She was able to identify where the photos came from—the nearby city of Abbotsford—based on a handful of graduation photos that were mixed in. There were also photos of a mushroom farm, but there are a lot of mushroom farms in Abbotsford, she told me, so she was unable to narrow her search any further. Still, she is grateful for her “creepy treasure,” she said, and plans to go randonauting again when the app stops crashing every time she opens it.

Other randonauts, reporting their adventures on Reddit, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok, have seen plenty worth documenting. None of the sights is so strange, really. That is, until it’s cut out of context, presented as the finding of a device that is somehow in cahoots with the universe: a window covered with a grid of Post-it Notes. A coyote standing in a cemetery at noon. Bones, snakes, toilets. But also a sheep, a bookshelf in the desert, a car wash with rainbow lights.

The randonauting community (and the term randonauting) existed before Lengfelder launched his app, and the generation of random coordinates used to take place with the help of a custom bot in the messaging app Telegram. (Lengfelder was part of the group that built that bot.) The randonauts subreddit was created in March 2019, and currently has more than 114,000 members. There, stories are incredibly wholesome—usually focused on rescuing injured animals or stumbling across meaningful locations that remind users of loved ones or their salad days. It’s the TikTok randonauts who want to see spooky stuff and catch aliens. They tend to trespass and many of them film unhoused people, sometimes calling them “creepy”—neither of which is in line with the “9 Tenets” of randonauting.

Still, the mainstream attention has been welcomed. The official randonauts Twitter account, which currently has more than 20,000 followers, recently claimed that the world is approaching a “paradigm shift, where the extraordinary will become ordinary,” as more and more people begin to believe in the possibility of minds influencing machines.

The basic premise of Randonautica—that your brain can influence a random-number generator—comes from controversial research conducted at Princeton beginning in 1979. There, the late engineer Robert G. Jahn spent decades exploring the largely derided hypothesis that people could use “micro-psychokinesis” to affect machines in very small ways. This theory—which has generally been dismissed by other scientists—is cited on the official Randonautica website, and extrapolated to suggest that a person can focus on any kind of specific feeling or noun and then be led to coordinates that somehow correspond to it. Brenda Dunne, Jahn’s lab manager for many years, told me in an email that this seemed possible to her: “I would predict that the results produced with the Randonautica app would demonstrate meaningful correlations only occasionally, but more often than might be expected.” Though, she added, the app has a “psychological aspect” that would prime users to notice coincidences and mystery.

In the course of my randonauting adventures, I asked the Stanford University statistics professor Brad Efron to explain randomness to me. “Randomness is more random than humans can contemplate,” he said, confusing me further and proving his own point. “It’s really easy to fool yourself that you’ve seen something very improbable.” In fact, strange animals and dead bodies and misplaced photos of moldy bread are as common as plenty of other things.

Still, the best randonauting story I heard came from 23-year-old Taylor Dickerson, who lives in Spokane, Washington, and it sounded pretty improbable—but true—to me.

Dickerson’s first foray into randonauting brought her and a friend into the woods, where she says they came across a pristinely preserved letter written on a sheet of notebook paper. It appeared to be a friendship letter, beginning, “I am writing this to inform you of how amazing you really are … I graciously think you are swell!” and signed by a man who—upon her Googling—turned out to have died weeks before. On Facebook, Dickerson and her friend say they were able to find the woman the letter was addressed to, and made arrangements to bring it to her.

“Sometimes I wonder if there are signs and messages around us but we just ignore them,” Dickerson told me. It had been raining in Spokane for days when she found the letter, apparently untouched. “I’ve read it at least 20 times. I think about how in a different reality, the note would’ve disintegrated into mush. It was like we were meant to find it.”

Of course, bizarre things happen all the time. Letters get dropped in the woods. Letters get found by 20-somethings who went out searching for a strange experience. People who write letters die in unexpected ways, and become mythological figures to other people who never even knew them. “The most amazing coincidence of all would be the absence of coincidences,” J. A. Paulos, a mathematics professor at Temple University, told me, upon hearing a summary of randonauting culture. “There’s so many ways to connect what you’re interested in—what you expect, what you fear—to where you end up.”

I use Randonautica almost every day now, in an effort to have more surprising after-dinner walks around Brooklyn. (I haven’t found any more bottles of pee.) I do realize that I could have just been going outside this whole time, and that it is arguably uncool that I need the incentives of a hokey piece of software to make me think regularly about doing so. But I like the app even more now that I know how it purports to work. It reminds me that demystifying the world can sometimes make it more spectacular.