This blog is part of CGD's Governing Data for Development project, which explores how governments can use data to support innovation, development, and inclusive growth while protecting citizens and communities against harm. David Medine is a member of the working group that guides the project.

Informed consent is premised on knowing how your data will be used and agreeing to those uses. So, when was the last time you read a privacy policy? Have you ever read one? Turns out even if you read just the privacy policies of websites you come across, it would take you 76 days a year! And that doesn’t include phone apps’ or internet of things devices’ policies. It’s no surprise that consent fatigue hits most people, so they just keep clicking to get past the notices. Ok, but what if you choose to spend a quiet Sunday afternoon just reading privacy notices. Would they make any sense? Probably not. In fact, college and law students in India were asked to read five popular websites’ privacy policies and then take an open-book test about their terms. These well-educated students got half the answers wrong, which is no surprise given how long and legalistic privacy policies are. Added challenges in developing countries may include whether the notices are written in consumers’ native languages and are viewed on devices on which it’s impractical to scroll through notices that are thousands of words long. A review of typical notices reveals how few choices consumers are given over how their data will be handled—it’s mostly take it or leave it.

Given all this, the notion that consumers provide informed consent regarding how their data is used . . . is clearly dead. But that doesn’t mean the privacy of their data has to be left unprotected. It just means we need to look elsewhere for data protections. It’s time to legally shift the burden of protecting data from individuals to providers. Two options for doing this are adopting a “legitimate purposes” test, only allowing data uses that relate to the product or service being offered or imposing a “fiduciary duty” requirement that data only be used in the customer’s interests.

A legitimate purposes test would limit companies’ use of data to what is compatible, consistent, and beneficial to consumers and could be reasonably expected based on the product or service being offered. For instance, it would enable providers to use an individual’s data to service accounts, fulfill orders, process payments, collect debts, control for quality, enforce security measures or conduct audits. Innovative uses of data would be permitted if consistent with the service for which the data were initially collected. Going beyond such uses, data could be used for more wide-ranging product development and innovation if they were robustly de-identified to reduce the risk of them being used in ways that are harmful to the individuals who are the subject of the data.

Alternatively, a fiduciary duty could be imposed on data collection and processing firms, requiring them to always act in the interests of, and not in ways detrimental to, their customers. Such legislation would mean that providers could not use data in ways that benefit themselves over their customers or share data with third parties that fail to put the customers’ best interests first. A fiduciary duty approach recognizes that poor people should not be required to give up their data protection rights to use digital services.

A pending Indian data protection bill follows both of these proposed approaches. First, following the fiduciary duty standard, the bill requires that personal data be processed only “in a fair and reasonable manner” that “ensure[s] the privacy of the individual.” This element of fairness would make sure that the individual’s interests are preeminent. Second, the bill states that data may be used only for the purposes the individual “would reasonably expect that such personal data shall be used for, having regard to the purpose, and in the context and circumstances in which the personal data was collected.” In other words, a legitimate purpose standard.

These approaches would limit the information asymmetries in many markets in which providers have a much greater knowledge than their customers about how customers’ data may be used. Furthermore, research at CGAP, the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, has shown that even during the pandemic the poor place a premium on the privacy of their financial data; they should not be required to give up their data protection rights to use digital services. Instead, legally obligating providers to act in the best interest of their customers can help establish trust and confidence among customers that their data are being used responsibly, making them more willing to try out new products and services.

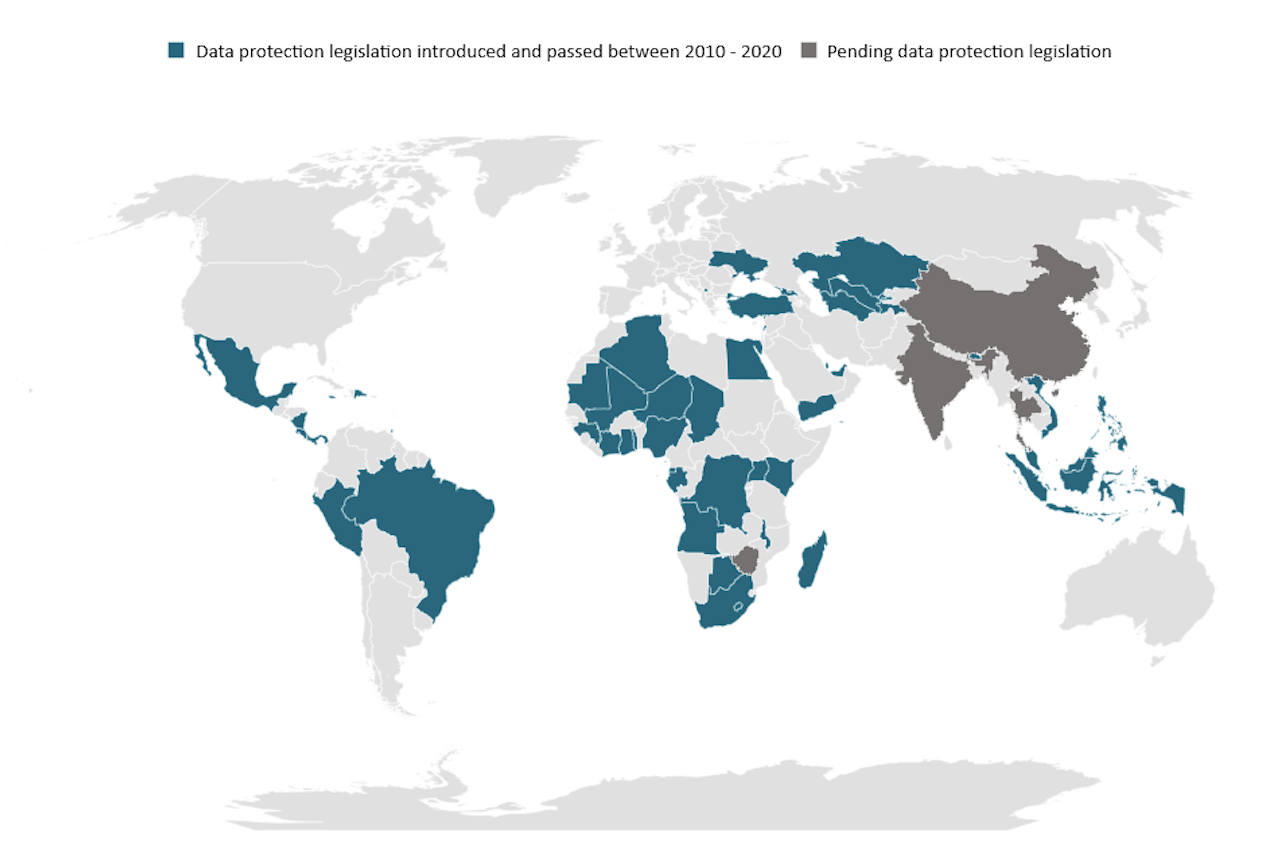

There is a growing recognition around the world that consent no longer works as a mechanism to protect personal data. Placing the burden on providers—and not individuals—to protect data privacy gives developing countries the opportunity to leapfrog to a future-ready data protection environment by shifting the paradigm for data protection in a way that both reflects the technological realities of the 21st century and considers the needs of its poorest citizens.

David Medine is a data protection consultant to CGAP.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.